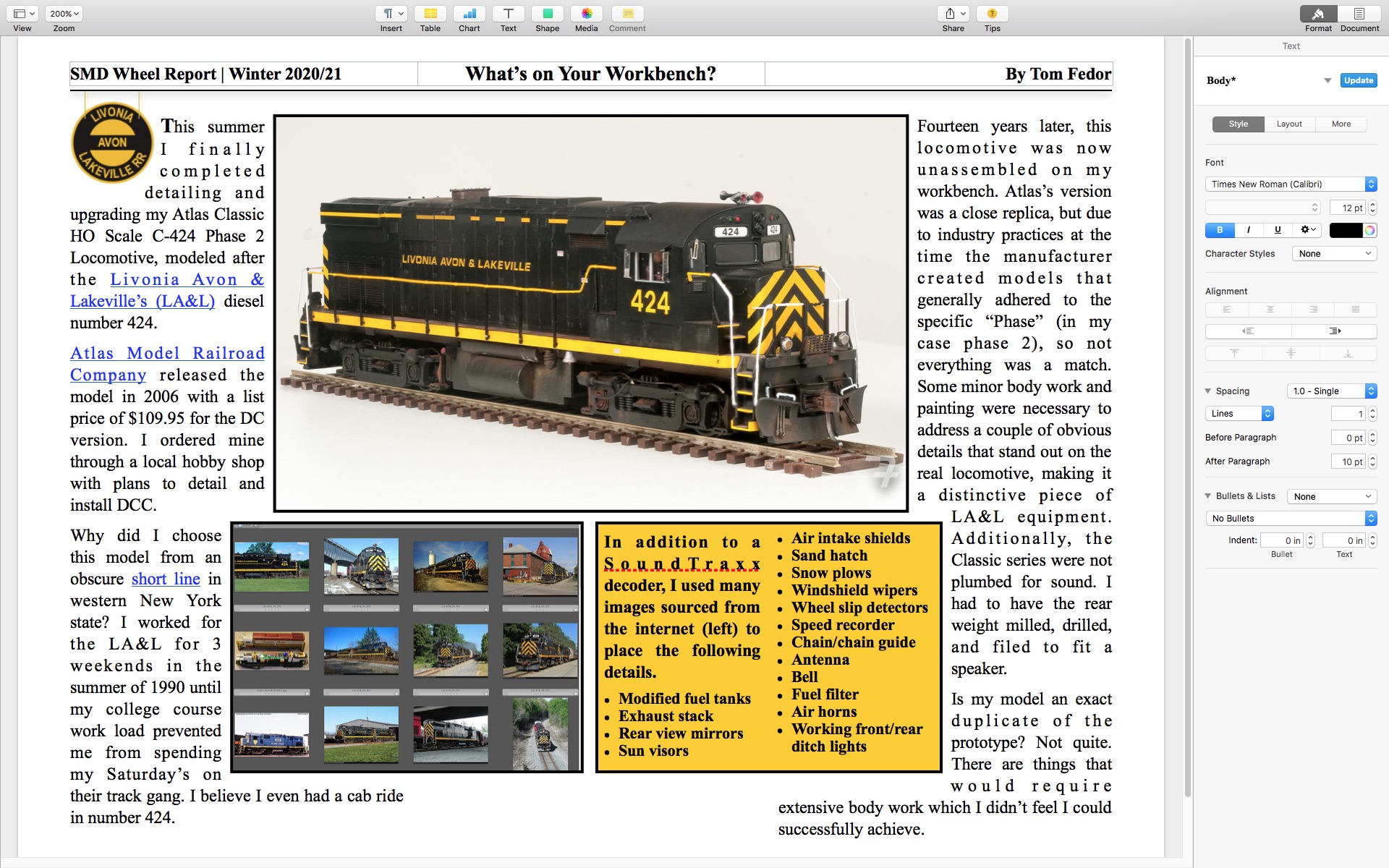

This summer I finally completed detailing and upgrading my Atlas Classic HO scale C-424 Phase 2 Locomotive, modeled after the Livonia Avon & Lakeville’s (LA&L) diesel number 424.

Atlas Model Railroad Company released the model in 2006 with a list price of $109.95 for the DC version. I ordered mine through a local hobby shop with plans to detail and install DCC.

Why did I choose this model from an obscure short line in western New York state? I worked for the LA&L for 3 weekends in the summer of 1990 until my college course workload prevented me from spending my Saturday’s on their track gang. I believe I even had a cab ride in number 424.

Fourteen years later, this locomotive was now unassembled on my workbench. Atlas’s version was a close replica, but due to industry practices at the time the manufacturer created models that generally adhered to the specific “Phase” (in my case phase 2), so not everything was a match. Some minor bodywork and paint were necessary to address a couple of obvious details that stand out on the real locomotive, making it a distinctive piece of LA&L equipment. Additionally, the Classic series was not plumbed for sound. I had to have the rear weight milled, drilled, and filed to fit a speaker.

Is my model an exact duplicate of the prototype? Not quite. There are things that would require extensive bodywork which I didn’t feel I could successfully achieve.

In addition to a SoundTraxx decoder, I used many images sourced from the internet (above) to place the following details.

- Modified fuel tanks

- Exhaust stack

- Rearview mirrors

- Sun visors

- Air intake shields

- Sand hatch

- Snowplows

- Windshield wipers

- Wheel slip detectors

- Speed recorder

- Chain/chain guide

- Radio antenna

- Bell

- Fuel filter

- Air horns

- Working front/rear ditch lights

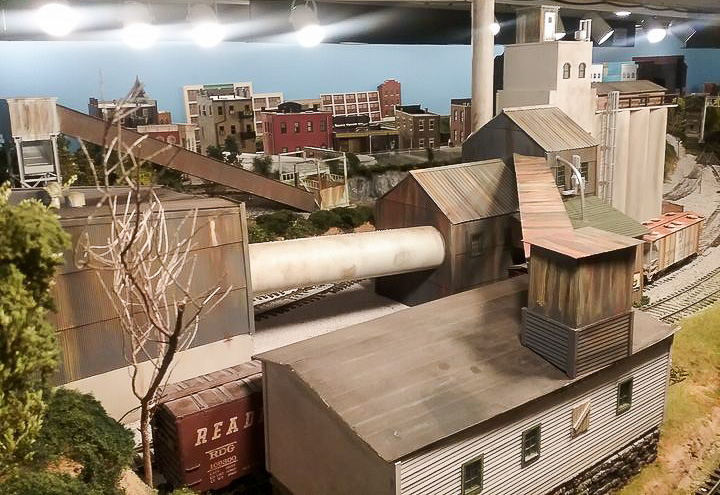

Rich Randall has been working on an O scale

Rich Randall has been working on an O scale  M

M Jay and his crew have done a lot of work this year. Find Jay online at

Jay and his crew have done a lot of work this year. Find Jay online at

Your Wheel Report needs photographs of current model railroad projects in progress or completed in this calendar year, 2020. Big or small; email a photograph and short description to Tom Fedor at

Your Wheel Report needs photographs of current model railroad projects in progress or completed in this calendar year, 2020. Big or small; email a photograph and short description to Tom Fedor at  Read more in the

Read more in the  Photography and essay by

Photography and essay by  Through this hobby, I am reminded that modern America was not borne out of Silicon Valley, but from workers and tycoons during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century in towns like Bethlehem, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore. For those of us interested in steel mills, coal mines, lumber mills and heavy industrial enterprises, research helps us dive deeper into the reality of that time. It’s important to learn about the organization of work in pre-internet America

Through this hobby, I am reminded that modern America was not borne out of Silicon Valley, but from workers and tycoons during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century in towns like Bethlehem, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore. For those of us interested in steel mills, coal mines, lumber mills and heavy industrial enterprises, research helps us dive deeper into the reality of that time. It’s important to learn about the organization of work in pre-internet America