By Tom Fedor

Our website is back up (along with this blog). Currently the web page includes just the basics and serves as a landing page for those interested in reaching the SMD. Links to documents like our by laws and archived newsletters will function as the data is migrated to the new server. Additionally the Winter Wheel Report has been published. Visit the website and locate the newsletters page to download this and archived editions. The “Train Rides” page is not included in the current edition. I made the decision to cut it due to space concerns and the fact that it’s content is readily accessible on line.

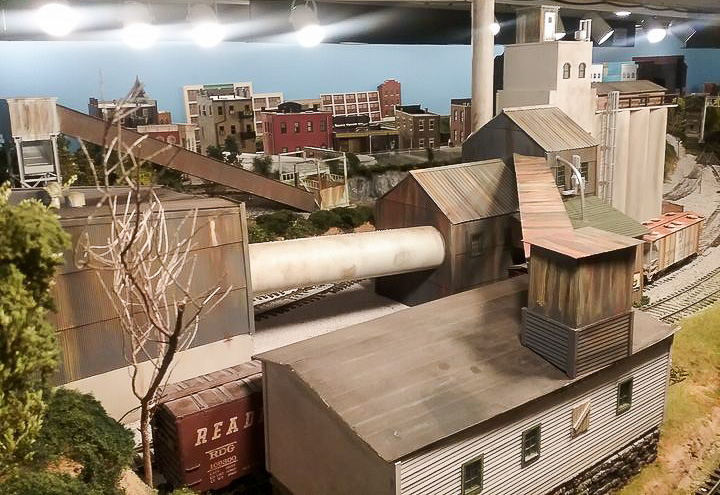

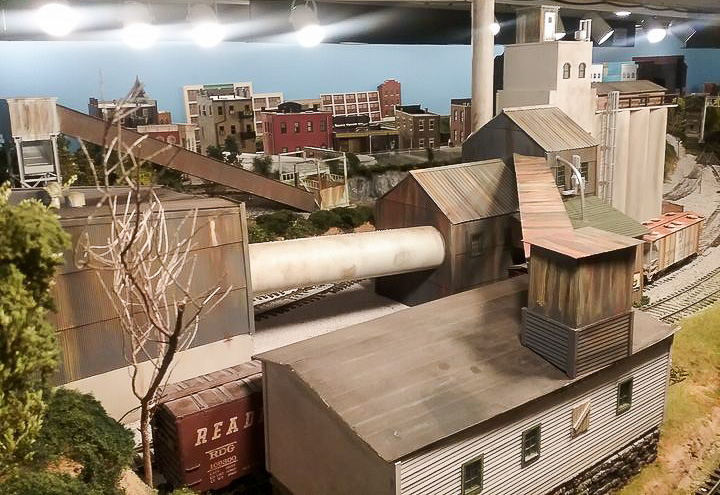

Rich Randall and friends have been very busy working on his Gettysburg, PA layout. I photographed Rich’s O scale Milwaukee Road for current the cover. Rich writes, “I am finally calling Avery East Yard finished, although there are still a few more small items to place. I received a lot of help with this project, especially from Leonard (Lee) Davis, master structure builder and scenery artist, and Tim Edwards who built the bunkhouse out of a San Francisco “Painted Lady” kit, and the depot addition out of a couple Ameri-Town track side sheds. Lee built the depot and other structures from scratch. Stu Gralnik of Model Building Services built the substation, which had to be 85% scale size to fit my space. It is amusing to me that after I crammed all the buildings into the scene, Tony Koester gave a clinic at the 2018 O Scale National Convention advising that the best way to compress a scene is to select a few key elements and space them so as to avoid cramming. Oh well! The catenary bents are made by Dave Hikel of Hikel Layouts & Trains. He assisted me in the construction of the catenary system. Tim Edwards made poles and sockets for installation in my various terrain. I still have a long way to go on the rest of my “Milwaukee Road Avery Division Point” O scale layout.”

By Harvey Heyser, III

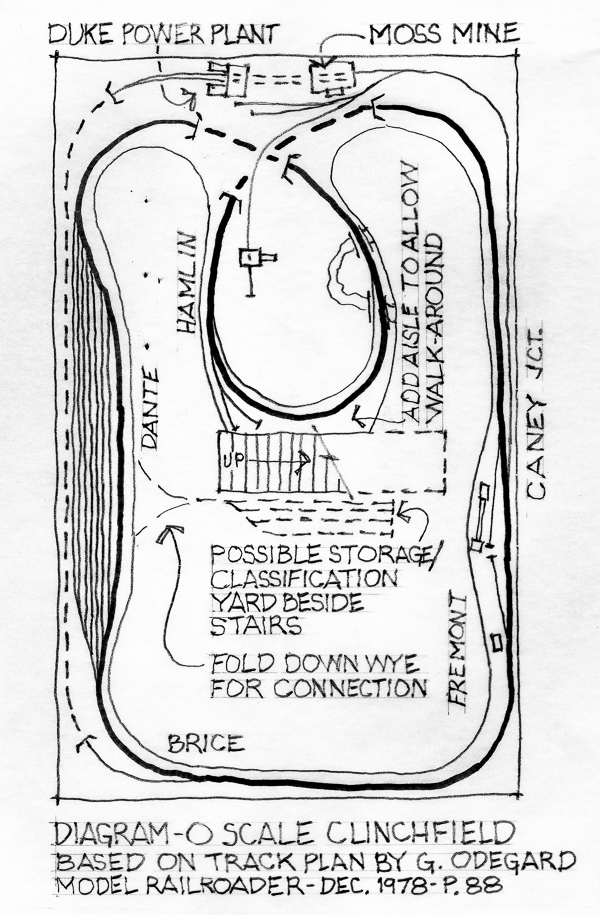

Many years ago, Model Railroader published an O scale plan version of their well known Clinchfield Railroad. (December 1978, p. 88.) That layout plan served as raw material for some thoughts about staging – thoughts that I find to have some general application.

Sized to fill an entire basement, the O scale Clinchfield featured a continuous oval mainline (around the walls of the basement with a peninsula) and two branches that came together in a loads-out/empties-in (mine/power plant) combination. The main yard at Dante featured eight (8) double-ended tracks (two of them the mainline and siding) and the connection with the power plant branch. On the opposite side of the basement, there was another town (Fremont/Caney Jct.) where the coal mine branch line took off to Moss Mine. The proposed operation of the layout featured heavy mainline freight traffic (especially coal drags), a few passenger trains, and some locals to serve on-line towns and the branches. There was no obvious place to put any staging/fiddle tracks. The question in my mind was how to provide meaningful traffic on the Clinchfield layout without any place to stage/fiddle. I wondered if it might be possible to use the yard (visible, rather than hidden, on-layout staging for the trains) and the trains themselves (in-train staging for the cars) to fulfill those functions.

Holding tracks and the concept of on-line staging: Many years ago, model railroaders embraced the concept of holding tracks as a way to extend the run times of trains. Trains went into the holding tracks and waited a prescribed amount of time before proceeding with their runs.

These holding tracks were often (but not always) hidden; however, unlike staging, holding tracks were regarded as part of the layout not “beyond the basement” as we currently regard staging. When the concept of staging caught on, holding tracks were sometimes repurposed as staging tracks. This conceptual connection between holding and staging leads to the concept of on-layout staging. Because the Clinchfield has no obvious place to locate conventional staging, we will be looking at “hiding” trains in plain sight on the layout – not in another room, not somewhere out-of-sight under the layout.

Types of mainline trains: I mentally reviewed the categories of mainline trains to be expected on the Clinchfield:

That creates the potential for eight (8) types of trains. In this situation, using one train to represent all trains of its type seemed a reasonable compromise.

On-layout staging for eight types of trains: Given the presence of six (6) available storage tracks in the yard, I wondered if they could serve as on-layout staging for all eight different types of trains. Types number 1 & 2, the coal trains (loaded and empty), would both need to be modeled. (The Clinchfield was a coal railroad, after all, and ran lots of coal drags.) If there were only a few passenger trains (#7 and 8 – reasonable considering the era modeled – late transition period) and if operating sessions represented only part of a day (say 8 or 12 hours), only one passenger train would run during each session. Then I considered the through freights and sweepers (#3, 4, 5, & 6). I realized that the main difference between them was the fact that through freights pass through the yard with their consists unchanged while the sweepers set-out and pick-up cars. Otherwise, both types of trains consisted of a mix of different kinds of cars, unlike the coal trains (hoppers only). So, an eastbound freight could stand in for both the through freight and the sweeper – the same for a westbound freight. That thinking resulted in the realization that five (5) trains could represent all the types of trains needed for a session. The yard had capacity to hold/stage the five trains needed to represent all required train types needed for a session’s mainline traffic with one track left over. The sixth track could then serve for making-up and breaking up local trains.

In-train staging

Coal drags & mainline freights:

Staging for coal drags: Both loaded and empty coal trains could represent all the session’s coal traffic. The cars in the two drags could be set out and picked up as needed. The east-bound drag could set out loads for the power plant on one trip. Then it could run light or hold in the yard until the local brought in loads from the mine. The next time the drag had to run, it would then be back to capacity. The sight of coal trains sitting in the yard is not unusual for coal hauling railroads. Perhaps the two coal trains should sit on the front two staging tracks.

Staging for through freights: Since these trains did not change consists, they simply could be considered to hold in the yard for other traffic. After they left, they could come back as different through trains or as sweepers.

Staging for sweepers: During a session, there were likely to be two sweepers – one east-bound and one west-bound. Each would set out and pick up a block of cars. But what would happen when sessions occurred frequently or when there were multiple sweepers during one session? The work for yard and local crews should not always seem to involve the same cars. Here I remembered that the yard tracks on the O scale Clinchfield were double-ended; cars could be set out and picked up from different ends of the train. The set out and pick up blocks could be close to the same size (say 1/3 of the cars in the train). Then, the trains would remain roughly the same length. If the set-outs always came off the front of the train and the pick-ups always went onto the back, the front end would be different, and the back end would be different each time they ran. Consequently, the sweeper would look different every time it arrived for each of six times around. (Remember Allen McClelland’s observation that we tend to notice the front and rear ends of trains the most.)

1st time through: block 1, block 2, and block 3 (Remove block 1; add block 4.)

2nd time through: block 2, block 3, and block 4 (Remove block 2; add block 5.)

3rd time through: block 3, block 4, and block 5 (Remove block 3; add block 6.)

4th time through: block 4, block 5, and block 6 (Remove block 4; add block 1.)

5th time through: block 5, block 6, and block 1* (Remove block 5; add block 2.)

6th time through: block 6, block 1*, and block 2* (Remove block 6; add block 3.)

(* assuming the exact same cars are brought in by the locals)

With typical (generic) motive power, there would be little chance that the repetition would be objectionable; in any case, the cars that the locals would pick-up would probably not be identical to the blocks originally set-out by the sweepers. A bit of fiddling between sessions (something you would get to do in an open yard at normal layout height, not under scenery or other tracks) could vary the sweeper consist so much that no one would notice.

Additional cars for locals: If additional cars were needed for local operations, pausing the session for a few minutes to change out some of the sweeper cars would certainly be possible. During the break, the yard could become a fiddle yard temporarily. When crews return, the consists of the trains would have “mysteriously” changed, and those trains would be ready for the next “act” in the drama that is an operating session.

On-layout staging for the rest of the trains:

Staging for passenger trains would require some sleight-of-hand. I would suggest leaving from the station, making a full circuit of the mainline oval, and then “hiding” on the back track of the yard rather than pulling up again to the station out front. The next run would be in a later session, so that you could turn the train (if needed) and start the next session with it somewhere more convenient (probably at the station).

Traffic staged on the mainline: For an additional train type (for instance, another passenger train), the session could easily begin with a train on the mainline if you could find a place to park/hide it during the session. Provision of a passing siding at Fremont/Caney Jct. might be the easiest way to provide an additional layover/holding spot.

Running mainline trains from on-layout staging: Treating the yard as if each end were a different place might make mainline trains more realistic. With that in mind, it seems to me there are several ways to handle mainline traffic:

None of these options would be particularly realistic for train crews but could serve to duplicate the flow of mainline traffic for yard and local crews. One way to make the experience less unrealistic would be to prevent mainline crews from walking from one end of the yard directly to the other end, thus forcing them to walk all the way around the layout room to pick up their next train. (See the discussion of my operating experiences at the end of this article.) Crew members who love to run trains might be volunteered for these mainline jobs. They might enjoy the experience enough to overlook its unrealistic aspects. (Modelers with an interest in automation of layout functions might be able to run mainline traffic by computer and use human crews for the other trains.)

Local operations: With both east and westbound locals needed to serve the mine and power plant, the sixth yard track could serve as the make-up/break-up track for these trains. Using in-train staging, the required cars would come off the coal drags and sweepers (in-train staging), which would also take the pick-ups when the locals return. The locals’ work would occur on the modeled portion of the railroad and would include keeping out of the way of mainline traffic.

Storage and classification: To make this scheme work, these functions would need tracks for holding and sorting the blocks of cars coming out of and going into the sweepers. Fortunately, the Clinchfield plan had open space beside the stairs in the middle of the basement for some single-ended yard tracks connected to the layout by a drop down wye. (See diagram at end of article.) This yard could also present the opportunity for some additional industry spots and the possibility for an interchange (another way for cars to come onto or leave the layout). With the wye in place, direct passage from one end of the yard to the other would be impeded, thus furthering the idea that both ends of the yard are “different places.”

Crew requirements (for this layout and this method of staging): The following crew assignments would be possible: Dispatcher, yardmaster, assistant yardmaster, yard crew, (2) two person local crews, (2) single person coal crews (frequent coal trains – switching to be done by yard crews), (1) single person through freight/sweeper crew (again switching to be done by yard crews), and (1) single person passenger crew. That totals twelve possible positions – a significant number for a layout lacking hidden staging/fiddle tracks.

What has been accomplished by this exercise? Thinking about the O scale Clinchfield, we have figured out how, with five (5) yard tracks, to accommodate seven or eight types of mainline trains staged on the layout within the yard. On-layout staging, coupled with using one train to represent all trains of its type, could provide heavy mainline traffic, including coal traffic (both loads and empties) moving in the appropriate directions. (The loads-out/empties-in feature eliminated the need to remove/insert loads.) With in-train staging, the blocks of cars needed for normal local operations would be ready to be set-out (giving the train capacity for any pick-ups). We have done this without “hidden” staging tracks or fiddle yards. (As noted previously, the O scale Clinchfield left no room in the basement for those tracks.)

These two concepts have great potential for many space-strapped model railroads such as:

One additional benefit, on-layout and in-train staging can be implemented either during the design stage or later when setting up an operating system. These ideas do not necessarily require revisions to layouts already built.

When thinking about my own experiences during operating sessions, I tend to focus my attention on my train and what it is doing. I pay relatively little attention to many of the things happening around me. So a yard full of trains is just one of those background things I tend to ignore. If I am assigned to run a through train that makes a complete circuit of the mainline loop, I walk all the way around the basement with my train. When my train returns to the yard, I approach from the opposite end of the yard. From this perspective, the yard I arrive at does not look exactly like the one I left from. That run finished, I get assigned to another train. If I have to walk all the way back around the layout room (rather than directly past the yard) to pick up that next train, I would again see the yard from a different perspective and would not notice what the yard contains. The contents of the yard are not really my business (on-layout staging), nor is the make-up of the trains in the yard (in-train staging) my business.

The ideas of on-layout and in-train staging make sense to me. There certainly are situations where they apply. I suggest they can work for you if you need them and give them a chance.

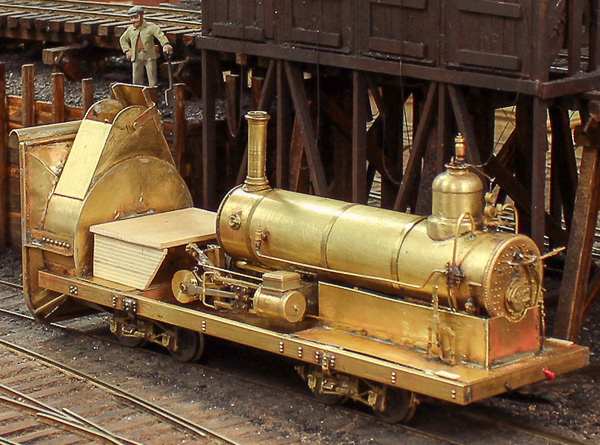

In 1888 the Colorado Midland Railroad bought a rotary snowplow from the Leslie Company. The original plow had a nine-foot rotary blade with a shroud 11 feet across that would clear a path wide enough for any Midland equipment. One of the more interesting aspects of the Leslie plow was the car body, which resembled a “greenhouse.” There was a crew area directly behind the blade and impeller wheel for the operators who had a full view out the front and sides thanks to all the windows. The body of the machine covering the steam engine to power the rotary was also lined with windows. One can only imagine all the broken glass that had to be repaired each winter

After a number of years in operation, the Midland decided to rebuild the body of their only rotary snowplow. In 1895 the railway’s shop converted the body of the machine to a more conventional and durable design, which included a minimal number of windows. The plow was numbered “08” until 1900 when the Midland bought a larger 11-foot bladed machine from the Schenectady Locomotive Company. The Leslie plow was renamed “Rotary A” and the new machine was designated “Rotary B,” and both machines survived until abandonment in 1918. The Midland Terminal Railway bought the Leslie machine in 1921, and it served that rail line until its demise in 1949.

The model represents the Colorado Midland’s Leslie snowplow after its rebuilding in 1895. Everything on the modeled snowplow is scratch built from sheet brass and bar stock, sheet wood for the sides, and castings for the window and truck side frames.

The front truck of the plow does not include brake shoes due to the accumulation of snow and ice as the machine fought its way through snow drifts that sometime were higher than the machine.

The rear truck does include brake shoes so there is some way to help stop the plow. The roof is made up of individual six inch wide boards covered in tissue paper with holes in the roof for the smoke stack and the steam dome with its relief valves and whistle. (Building the tender is the next order of business.)

Looking at the model from the rear with the car body removed, one can see all the workings that make the blade turn. (There is a motor under the boiler and all the mechanisms work, even producing a breeze out the exhaust chute.) While some detail work remains, the wood platform is for the operator to supervise the movement and speed of the plowing operation. He is also, and equally important, tasked with the responsibility to set the exhaust shroud for throwing the snow out to the left or right side of the train. The cylinders are set in a reverse position so they can power the blade through a set of gears. Due to blowing snow, shrouding had to be used to surround most of the boiler and the firebox to keep the working area as clean as possible. It would take at least a two-man crew to operate the boiler with its “Johnson Bar,” injectors, and to shovel coal. But, one of the most important jobs would be to operate the whistle, which was the means of communications between the plow operator up front and the crews in the four or five locomotives pushing from behind the snowplow’s tender.

<https://www.gofundme.com/BSME-needs-locomotion>